The question of whether or not Eric will exact bloody revenge switches the film’s dramatic register a third time, leaving the viewer without a satisfying love story (Kidman is lovely in a role that asks too little of her) or a penetrating character study. For me, this is where The Railway Man, which begins a little like Brief Encounter, then veers toward Bridge on the River Kwai (explicit references are made to both films), got a lot less complicated. (Lomax, who consulted on the film, indicated that he would not be interested in watching the finished result, lest the representation of his suffering reignite bad memories.)įinlay presents another option: He discovers that one of their captors, a translator, is still alive and leading guided tours of the old labour camp. Trauma must be dealt with somehow, but reliving it for your wife is not necessarily the best or only option.

Patti seeks out Eric’s fellow veteran and best friend Finlay (Stellan Skarsgard), who tells her to back off: 'There are some things," he says, 'so humiliating and shameful that I’m not sure you’d ever want to talk about him." Despite being wildly out of fashion even in 1983, to me the statement makes a lasting sense. We are meant to understand the kind of suffering that can turn healthy young men, as Eric says, into 'an army of ghosts." When the Japanese discover the radio receiver Eric managed to cobble together, he is singled out for two weeks of barbaric torture-beatings, a tiny bamboo cage, and mock-drowning viewers will recognise as 'waterboarding."Įric, still shaken by nightmares 40 years later, shuts down when Patti asks about Singapore, and sometimes lashes out. The Japanese put most of these men to work on a railroad stretching from Thailand through the Burmese jungle, and Teplitzky does not shy away from depicting the uncommon cruelty with which the Japanese ran their forced labour camps. A vicious battle leads to the surrender of some eighty thousand British, Indian, and Australian troops, Eric among them. It’s then that The Railway Man jumps back to 1942, when Eric (delicately played by War Horse’s Jeremy Irvine) was a service officer stationed in Singapore. Soon the pair wed, and begin a surprise third act. The railway offers Eric a world to organise, and on one particular trip it offers him Patti, a pretty brunette who takes an interest in Eric despite his rather flat, taciturn first impression. The Lomax we first meet is 60-ish and rumpled, a budding codger and practiced 'train enthusiast." His obsessive knowledge of the British rail system-which trains to take where, at what time, given any circumstance-suggests a mind vigilantly aware of its options, of the best way out. As The Railway Man shows, the culture of silence runs deep. There also remains, in military culture, a stigma attached to asking for help.

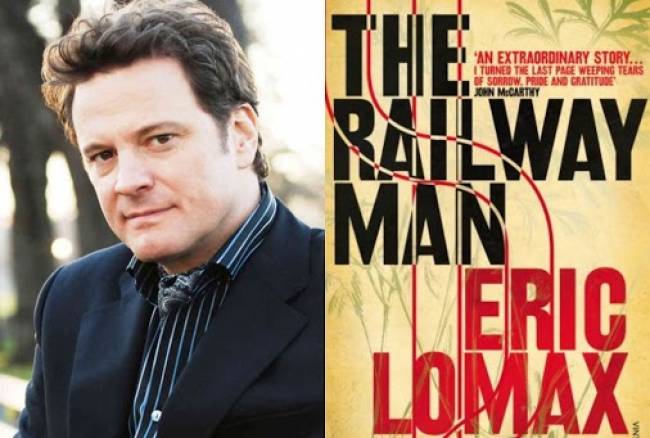

In the United States, veteran suicides have reached all-time highs effective treatments are either not available or not available enough. Though post-traumatic stress disorder is a recognised psychiatric diagnosis, Western military institutions are only now beginning to address a new generation of veterans unable to function on returning home. Traditional in tone and execution but modern in its resonance.Ī gala presentation at this year’s TIFF, The Railway Man is traditional in tone and execution but modern in its resonance. Directed by Jonathan Teplitzky, The Railway Man focuses on Eric’s late-life marriage, suggesting it was love that pressed him to finally deal with his war experience. Now, less than a year after Lomax’s death (at age 93), comes the feature adaptation, in which Colin Firth plays Lomax and Nicole Kidman his wife Patti. Lomax published his autobiography, The Railway Man, in 1995 that same year saw the release of a documentary about his experience, Enemy, My Friend, and a television dramatisation starring John Hurt.

TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL: The life story of Eric Lomax, a British prisoner of war tortured by the Japanese during World War II, has been covered from several angles.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)